Innovation does not happen in isolation; it is a battleground where ideas clash, rivalries ignite, and the pursuit of ownership shapes the future. Behind the technologies we rely on every day lie stories of groundbreaking discoveries entangled in fierce legal disputes, where patents have been both catalysts for progress and obstacles to competition.

But how much do we really know about the battles that define the modern world? Welcome to “Patent Feuds: The Untold Battle That Shaped Innovation,” a deep dive into the untold stories of ambition, controversy, and the relentless fight for technological dominance. In this series, we will explore the rivalries that shaped industries, the inventions that sparked legal firestorms, and the lasting impact of Intellectual Property on the world as we know it. Get ready to uncover the drama, the stakes, and the ideas that changed world history.

A Sticky Situation That Sparked a Patent Feud

This is the story of burnt rubber, scientific serendipity, and a cross-continental clash that shaped the modern rubber industry.

Rubber products have become an integral part of our daily lives, especially in the form of car tires. Beyond that, rubber is used in a wide range of applications. However, natural rubber posed a major challenge it would harden and crack in cold weather and become sticky or melt in the heat. This inconsistency made it difficult for manufacturers to rely on rubber for durable products. But innovation often arises from adversity. It was during this period that Charles Goodyear accidentally developed the vulcanization process, revolutionizing the rubber industry.

We do not claim any copyright in the above image. The same has been reproduced for academic and representational purposes only.

The Vulcanization Revolution: The Cure for Crude Rubber

Vulcanization, the process of heating rubber with sulphur, solved this. It cross-linked the rubber molecules, dramatically improving elasticity, durability, and thermal stability. It was a game-changing innovation, making rubber suitable for tires, seals, hoses, shoes, and more.

But who truly discovered it first?

Accident Meets Genius: Charles Goodyear’s “Eureka” Moment

Charles Goodyear was a struggling inventor obsessed with rubber. Despite repeated failures, he remained convinced that rubber’s flaws could be fixed.

In 1839, Goodyear accidentally dropped a mixture of rubber and sulphur onto a hot stove. To his amazement, the rubber did not melt it hardened into a flexible, stable form. He had stumbled upon vulcanization, though he did not yet understand the chemistry behind it.

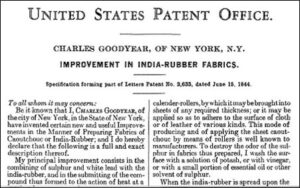

We do not claim any copyright in the above image. The same has been reproduced for academic and representational purposes only.

Goodyear spent the next few years perfecting the process and demonstrating its applications. He received U.S. Patent No. 3,633 for the vulcanization of rubber in 1844.

We do not claim any copyright in the above image. The same has been reproduced for academic and representational purposes only.

Goodyear’s Samples Reached Europe

Before filing a U.S. patent in 1844, Goodyear sent vulcanized rubber samples to various individuals and companies, including potential partners and manufacturers in Europe, hoping to spark business.

Unfortunately, Charles Goodyear had disclosed some of his findings to acquaintances and visitors before filing, a decision that would come back to haunt him.

The British Twist: Hancock Enters the Scene

One of these samples, whether directly or indirectly, landed in the hands of Hancock. Intrigued by the sample’s extraordinary properties, Hancock and his associate, chemist William Brockedon, began a methodical analysis.

Through reverse engineering, they discovered the crucial secret: sulphur was the key ingredient. Using this insight, Hancock reproduced the vulcanization process successfully in his own lab.

Seizing the opportunity, Hancock moved swiftly, and on November 21, 1843, he filed a patent for vulcanized rubber in the United Kingdom a year before Goodyear secured his U.S. patent, describing it as a process of improving rubber’s properties using sulphur and heat.

At that time, Goodyear had not yet filed any patent in Britain, nor was there any international agreement like the modern Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) to protect inventions globally. This gave Hancock a significant legal edge: he secured the British patent rights legally and strategically before Goodyear could react.

Legal Tangles and Verdicts: Who Came Out on Top?

When Charles Goodyear realized that Thomas Hancock had patented the vulcanization process in Britain, he pursued legal action, claiming that he had invented the process years earlier in the United States. Goodyear argued that Hancock had obtained and reverse-engineered a sample of his vulcanized rubber and thus was not the true inventor.

The British courts, however, were bound by the legal principles of the time. Under British patent law in the 1840s, priority was given to the first person to file a patent, not necessarily the original inventor. Since Hancock had filed his patent in the UK on November 21, 1843, and Goodyear had not filed any British application before that, the court ruled in favor of Hancock.

Goodyear never patented his process in Britain, a major tactical oversight. When he tried to challenge Hancock’s British patent, the legal system sided with Hancock, mainly because:

- Hancock’s patent was filed earlier in the UK.

- Goodyear had failed to maintain secrecy before his U.S. filing.

- There was no international patent protection at the time.

In contrast, Goodyear’s U.S. patent (granted in 1844) was never successfully challenged, and he retained full rights in the United States.

As a result, Hancock legally held the rights to vulcanization in Britain, while Goodyear retained control in the United States.

Patents, Priority, and Pitfalls: Lessons from the Vulcanization Feud

The Goodyear-Hancock patent feud is more than just a historical squabble; it is a timeless lesson in the power of intellectual property strategy.

Charles Goodyear was the true inventor, but his delayed international patent filings cost him dearly. On the other hand, Thomas Hancock, though not the original creator, acted swiftly and secured patent rights where it mattered in Britain.

The courts didn’t ask who invented first; they looked at who filed first.

Key Takeaways for Modern Inventors:

- File early, file smart: In today’s world of global innovation, timing your filings and protecting your work in the right jurisdictions is everything.

- Innovation alone is not enough: Legal protection determines who profits from the invention.

- Documentation and diligence matter: Proper records and strategic foresight could have helped Goodyear defend its rights beyond the U.S.

In the end, Goodyear gave the world a game-changing technology, but Hancock got the British market. Let this feud be a reminder: in the world of patents, the race is not just to the brilliant but to the prepared.

Goodyear had the spark of genius, but Hancock had the pen at the right place and time. In the patent world, brilliance needs backup, and that backup is strategy.

R K Dewan & Co. offers end-to-end legal support in Patent and IP Litigation, with a strong emphasis on Invalidation Search and urgent interim relief strategies in commercial disputes. Our team excels in navigating the nuances of Section 12A of the Commercial Courts Act, particularly in Intellectual Property matters where time-sensitive injunctions are critical to prevent ongoing infringement. With decades of litigation experience and technical expertise across pharmaceuticals, FMCG, technology, and creative industries, we ensure that clients receive precise invalidation support—from prior art analysis to courtroom strategy—helping them safeguard IP assets and enforce rights swiftly and effectively.