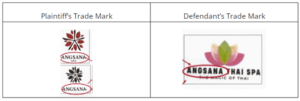

The recent Delhi High Court case involving Banyan Tree Holdings Ltd. (Banyan Tree) against Angsana Thai Spa (ATS) raises an interesting question regarding jurisdiction. While I agree with the Court’s decision wherein it granted a permanent injunction in favour of Banyan Tree against ATS for using the mark “ANGSANA”, I have certain reservations concerning the aspect of the jurisdiction.

Brief Facts of the case:

Banyan Tree Holdings Limited the Plaintiff, (Banyan Tree) is a part of the Accor Group of Hotels. It is a Singapore based entity. Banyan Tree owns the registered trademark ‘ANGSANA’ in India since 2000. It is seen that Banyan Tree conducts its business in India through “Angsana Oasis Spa & Resort” located in Bengaluru; however, Banyan Tree does not have any spa or resort in Delhi. Therefore, it can be said that Banyan Tree is not doing any business under the mark “ANGSANA” within the jurisdiction of the Delhi High Court.

Banyan Tree was aggrieved by the fact that ATS was using the mark “ANGSANA”. Banyan Tree filed a suit in the Delhi High Court.

The term “ANGSANA” is native to Sanskrit language in which the word ‘Ang’ means body and ‘Aasana’ means a relaxed self-aware posture.

However, it is presumed that for legal convenience Banyan Tree filed a suit and sought injunction against ATS, in the Delhi High Court. Banyan Tree argued that the spa had an online presence and used the “ANGSANA” trademark on their website which was accessible in Delhi and therefore potentially caused confusion and harm to their reputation.

The Delhi High Court, while accepting jurisdiction, considered the “accessibility of evidence and witnesses”, as a core reason. The Court, in its wisdom considered Delhi to be a convenient forum for both parties in spite of the fact that the Defendant was carrying on business only in Bengaluru and that the Plaintiff had only one outlet again in Bangalore. Therefore, the decision of the Delhi High Court to consider Delhi as a convenient forum is to say the least, surprising! On 23/12/2022 the Court was pleased to grant an an ex partead interim against the Defendants from using the mark ‘Angsana Thai Spa’, and ordered for locking, blocking, and suspending the domain name angsanathaispabangalore.com.The records don’t show that the Plaintiff had produced any evidence which establishes that any person in Delhi had even enquired or availed of the Defendant’s services. The Defendants did not contest, however it appears that the listing for ATS continued on JustDial, which is an organization on which a listing cannot be controlled.

Source – Judgement

Thereafter, Banyan Tree filed an application under Order XIII-A CPC and sought for a summary judgement. The Court passed a decree of summary judgment and permanently restrained Defendants from using the mark ‘Angsana’. The Court also ordered for removal of Defendant’s listing on Just Dial and awarded Rs. 12, 82,580 as actual costs to the Plaintiff and directed the domain name www.angsanathaispabangalore.com to be transferred to Banyan Tree.

Critical Analysis:

The primary issue to be considered in this case is whether the Delhi High Court had jurisdiction to adjudicate upon a trademark infringement case filed by Banyan Tree against ATS, operating in Bengaluru. I have no issue with the Courts ultimate finding that the Defendant was violating the Plaintiff’s registered Trademark. However, some aspects need to be taken with a pinch of salt:

- Limited Territorial Jurisdiction and Lack of Territorial Nexus: ATS is located and operates only in Bangalore, Karnataka. In my humble opinion merely having a website that is accessible in Delhi or advertising or posting on social media might not establish a strong enough presence to justify a lawsuit in the Delhi High Court. Section 134 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 provides that a suit for trademark infringement or passing off can be brought before a Court having jurisdiction;

- where the plaintiff resides/carries on business or

- where the defendant resides/carries on business or

- where the cause of action arises

In the present case, none of these limbs of jurisdiction appear to be satisfied: The Plaintiff is a Singapore based entity, and has only one business activity in Bangalore in India; The Defendant resides and carries on business in Bangalore; it has not offered any services outside Bangalore. Therefore the cause of action arises solely in Bangalore.

- This is a classic case of forum Non Conveniens: Forum Non Conveniens is a legal term that refers to a Court’s power to decline jurisdiction over a case when another forum would be more convenient or appropriate for the resolution of the dispute. It is often used in cases where the parties involved are located in different jurisdictions, or where the subject matter of the case has little connection to the forum where the case was initially filed. Section 20 of the CPC allows courts to decline jurisdiction if it is an inconvenient forum. In the present case, the Plaintiff itself has a presence and operates in Bengaluru without any tangible business activity in Delhi, and moreover Bengaluru is where, the alleged infringement has primarily occurred. Hence, the Bangalore District Court would be the most convenient forum for trying this case. Filing the lawsuit in Delhi might be seen as an attempt to forum-shop for a potentially more favourable outcome.

- Burden and Potential Prejudice to the Defendant: Forcing ATS to contest in Delhi may be seen as an unwarranted burden. Litigating in Delhi away from its home base and also surprisingly away from the home base of the Plaintiff could have put ATS “as well as” the Plaintiff at a disadvantage in terms of resource access and witness availability.

- Ignoring Supreme Court Precedents: The Delhi High Court’s decision to accept jurisdiction seems to deviate from established Supreme Court precedents like “New Holland Tractors (India) Ltd. v. M.S. Agrotrac & Anr.” (2013) and “S.L. Malhotra & Co. v. Maharaja Dharmendra Singhji & Anr.” (2020) which have emphasized the importance of proper territorial jurisdiction in trademark infringement matters.

This judgment highlights the complexities of jurisdictional issues in trademark disputes and if upheld, could set a negative precedent for future trademark infringement cases, potentially encouraging forum shopping and unnecessary litigation burden on Defendants. A more nuanced analysis of Section 134 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999and its interplay with Section 20of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, along with an evaluation of the specific facts of the case, could have provided a more robust foundation for a proper jurisdictional decision.